Hamming’s reflection

I have a rare copy of the 1952 Bell Labs directory. […] What is astounding to me about this directory is that it seems that almost everyone in it became famous. I find this incredible. Perhaps the world was a much simpler place then, where every “plink, plank” of technology resulted in a great invention. Or were our predecessors giants, whom we have no hope of matching? […]

In contrast, when I look at the 1986 Bell Labs directory, the names on the pages swim before my eyes. […] But here is the question: If I were to look at this same 1986 directory in the year 2020 (another 34-year time lapse), how would I see those names?

—Robert W. Lucky ↗

In the March 1987 issue of IEEE Spectrum Robert W. Lucky reflected on his time at Bell Labs. He had joined in 1961 and spent the following three decades within the labs. Recalling his years in the early 60s, “I was intimidated and awestruck by the famous people who drifted by the hallways.”

Flipping through the first three pages of the 1952 directory, “I see a profusion of legendary names; I see four people who went on to win Nobel prizes, four who would become presidents of large corporations, a college president, a dean or two, and numerous vice presidents. I see the inventors of the transistor, the laser, information theory, coding, and negative feedback. What kind of a world was this, where famous names were disguised at the time as nobodies?”

In comparison to his 1961 vintage, “My own generation has had two decades to prove itself. Many of my contemporaries have made names for themselves, but somehow they don’t seem as notable as those illustrious names of the past.”

He received a letter from Richard Hamming in response. It is worth reproducing in its entirety.

In answer to your “Reflections: The Footsteps of Giants,” I too have had a lot of time to think of what I lived through at Bell Labs during my 30 years, 1946–76, which is the time you are talking about.

I claim that the period was unique and it is not likely to be duplicated.

I was one of the four “Young Turks,” and it appears both that we saw ourselves that way, and that management independently saw us that way. The four were: Shannon, Ling, McMillan, and myself, the middle two having risen to vice-presidents. That leaves me! We were all very close in age and hence had a common background from society. Let me document the features that seem to have mattered.

- We were all of an age to be deeply affected by the Great Depression, and as a result felt that we owed the world a living, and not that we had only to behave ourselves and the world would be obliged to take care of us. This is the fundamental attitude that explains a lot of our drive to succeed.

- We had all of us been forced (quite willingly!) during the war to engage in activities that were not what we would have chosen in normal times, and we were forced to learn a lot of strange, new things in science that were unrelated to our past training. We were broadened in our outlooks.

- We had seen the almost immediate consequences of advances in science and engineering that we had been involved in, and as a result, we had greater reason to believe that striving to discover new things was worthwhile.

- Our management had also been through somewhat similar experiences, and probably were more sympathetic to our unconventional behavior than would otherwise be true. Certainly they deserve much credit for letting us do the things we did the way we did them.

- We had seen comparatively young people direct important work and bear responsibilities, and some of us had indeed risen early to positions of responsibility.

- Due to the tremendous war effort (and we felt that unlike in any other war America was directly threatened in WWII) science had made remarkable strides, and there was widespread recognition that science was important—more so than now. It was an exciting time to be a scientist or engineer.

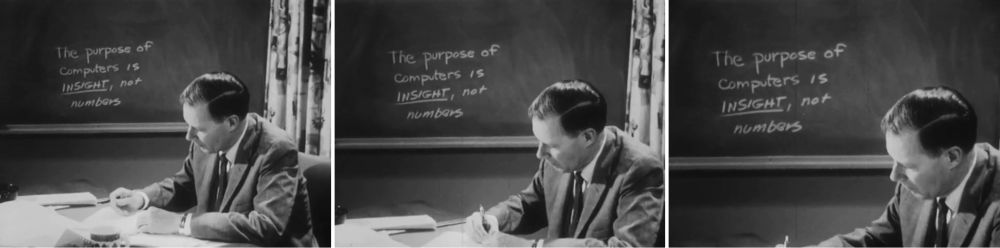

- Perhaps the coming of the computer should also be regarded a unique stimulus to creative science.

My conclusion is that you cannot again create the situation that gave rise to that remarkable outburst of creativity.

The next group of people in the department that were hired were perhaps more able, better educated, etc. but collectively they did not equal our productivity. The average of about seven years in age apparently made a great deal of difference, but also the opportunities we had were to some extent denied to them.

Yes, it was a unique time—I was lucky!

February 2024